Who was Roberto Assagioli?

Short biography of the founder of Psychosynthesis (*)

Who was Roberto Assagioli? Some might say “one of the very first Italian psychoanalysts”; others might say “a passionate scholar and a practitioner of meditation”. Assagioli was a pragmatist, but also an astrologer; a pioneer of humanistic and transpersonal psychology, but also a mystic; a precursor of psychosomatic medicine, an adventure lover, a psychiatrist, an esotericist, a scientist, an orientalist, an educator, a spiritual guide..

So, who was Roberto Assagioli really? Let’s proceed with a fundamental operation in Psychosynthesis and distinguish the different roles, the different interests, the various faces of Assagioli, from its most intimate and authentic essence. Then we can say that, in the end, Roberto Assagioli was just Roberto Assagioli, simply himself, a unique and original being, just like each of us.

When I was writing my second book [1] and thinking about how to tell its story, I let myself be guided by the symbolic image of the development of a tree and I therefore divided it into four parts:

- “Sowing”

- “Sprouting”

- “Pruning”

- “Blossoming”

Sowing (1888-1918)

Roberto Marco Grego was born in Venice to Jewish parents. At the age of two, he suddenly lost his father. After some time, his mother remarried with the doctor Emanuele Assagioli, from whom he received his surname. In 1904, the family moved to Florence to allow him to attend in the Faculty of Medicine.

As emerges from the recent publication of an interview granted a few months before his death [2], Assagioli was a very curious, lively young man, gifted with a great sense of humor and attracted to travel and adventure. For example, during a trip to Russia in the company of a friend, Madame Bogrova, who had headed a revolutionary woman’s student organization, he found himself indirectly involved in the assassination of Prime Minister Stolypin: the killer was a cousin of his friend. The way he describes the whole thing is amusing. Read it if you have the chance!

Already vast and diversified cultural interests characterized the university years. Three in particular, the lines of research that Assagioli will then deepen throughout his life:

- american psychology, in particular the pragmatism of William James;

- psychoanalysis and psychotherapy;

- the spiritual traditions of many cultures, especially the oriental ones.

Assagioli attended the Florentine avant-garde movement by collaborating with Papini and Prezzolini in the editorial staff of their magazines: the “Leonardo” and “La Voce”. He wrote of that experience: “The literary avant-garde had the great merit of introducing into the Italian culture, at the time somewhat provincial, the thought of some of the most important philosophers and psychologists of the time” [3]: Nietzsche, Freud, Bergson, and especially the American pragmatism of William James and Emerson. The avant-garde openly criticized the materialistic approach of the science of the time and they said: “this science, mechanical and rationalist certainly serves many very useful purposes but has very little to tell us about the ultimate and existential problems of the human being”.

At the same time, Assagioli travelled all over Europe to study with the major psychiatrists of the time: Claparède and Flournoy in Geneva; Kraepelin and Jones in Munich; Bleuler and Jung at the Burghölzli in Zurich. Thus, he come to know of the theories developed by Freud and, although very young, he fully understood their revolutionary significance. A great merit if we think how psychoanalysis was then opposed in Italy. Assagioli will in fact be (and he was only 20 years old!): the first Italian to translate some of Freud’s articles; the first Italian admitted to the International Psychoanalytic Society; and the first student to graduate with a thesis on the subject. Thesis written right under the supervision of Carl Gustav Jung with whom he will then maintain friendly relations throughout his life.

However, right from the start – thus anticipating by decades many of the topics highlighted later by humanistic and transpersonal psychology – Assagioli identifies the limits and weak points of psychoanalysis. He believes that “in the psychic building there are not only the unhealthy subsoils to be restored (those so well underlined by Freud), but also the various floors, and finally the luminous attics with large terraces, where you can receive the life-giving rays of the sun and in the evening contemplate the stars…”.

In fact, the birth of his great interest in the spiritual, philosophical and esoteric traditions of many cultures dates back to this very period. He takes Sanskrit lessons to read the classics of Eastern spirituality, which show him without any doubt: “how much the introspective psychology of the East, especially regarding the higher states of consciousness, it has reached such a point of complexity and depth that it far exceeded contemporary psychology” [4].

Sprouting (1918 – 1937)

In the second part of his life, which I called “sprouting”, the numerous stimuli accumulated previously begin to take shape. In 1922, he married Nella Ciapetti, and a year later their only son, Ilario, was born. In the same period, they moved from Florence to Rome where Assagioli began to carry out the activity of psychiatrist and psychotherapist and founded the Istituto di Cultura e Terapia Psichica.

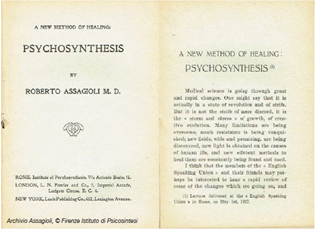

1927 is an important date because Psychosynthesis is officially born. Assagioli publishes in English the booklet “Psychosynthesis – A new method of healing” in which he outlines some significant points of the psychosynthetic model: the importance of body-psyche interaction; the need to integrate systematically various approaches and methods. The goal is no longer “simply” the elimination of symptoms, but the formation or reconstruction of the entire personality.

For Assagioli it was certainly very important to ask and study: “How and why do we get sick and develop symptoms?” But it was equally important, and perhaps even more, to ask and study: “How and why are we healthy, are we well? How and why do we grow, mature and realize ourselves more fully? “

For this reason, Psychosynthesis does not find its application only in the treatment of psychic and psychosomatic disorders. Psychosynthesis is also a method for education (for children and adults ongoing education), for self-development (for personal and spiritual growth), for the harmonization of interpersonal relationships (as a couple, between parents and children, teachers and students, between managers and employees) and social relationships (of increasingly large groups of human beings).

“Each of us can make the living material of his personality an object of beauty through which the transpersonal Self can manifest” R. Assagioli

The importance of these different fields of application lies in confirming the pragmatic nature and versatility of the psychosynthetic method. That’s why there are also very different professional figures who are trained in Psychosynthesis: doctors, psychiatrists, psychotherapists, counselors, but also managers, coaches, social workers, nurses, teachers, and so on.

Pruning (1938 – 1951)

“Pruning” is the title of the third part of his life since this is certainly a very difficult, troubled period. Assagioli was Jewish and during Fascism, he suffers racial persecutions. In 1938, he was forced to close the Institute. In 1940 he was even denounced, arrested and imprisoned on charges of being a “pacifist and an internationalist” and, after this, he was forced to hide in the mountains with his son Ilario to escape the Nazis.

Recently, the Istituto di Psicosintesi in Florence published the book “Freedom in Jail” [5] which collects the memories he wrote about his prison experience. Here is an illuminating extract:

“I realized that I was free to take one or another attitude towards this situation, to give one or another value to it, to utilizing it or not in one or another way.

I could rebel internally and curse; or I could submit passively in a vegetative state; or I could indulge in an unhealthy pleasure of self-pity and assume the martyr’s role; or I could take the situation in a sporting way and with a sense of humor, considering it as novel and an interesting experience (what Germans call an ‘Erlebnis’). I could make of it a rest cure; or a period of intense thinking either about personal matters, reviewing my past life and pondering on it, or about scientific and philosophical problems; or I could take advantage of the condition in order to submit myself to a definite training of psychological faculties, to make psychological experiments upon myself; or finally as a spiritual retreat.

I had the clear perception that this was entirely my own affair and that I was free to choose any or several of these attitudes and activities; that this choice would have definite and unavoidable effects, which I could foresee and for which I was fully responsible. There was no doubt in my mind about this essential freedom and power and the inherent privileges and responsibility: a responsibility toward myself, toward my fellow mankind, and towards life itself or God.”

At the end of the war, Assagioli resumed his activities. Unfortunately, his son, Ilario, died of pulmonary tuberculosis at just 27 years old, also due to the hardships suffered during the war.

Blossoming (1952 – today)

Despite all these difficult trials, Assagioli continued to spread and develop Psychosynthesis. In fact, the last period of his life, which I have called “blossoming”, saw the birth of numerous centers scattered all over the world and the first official acknowledgments of his work:

- 1961, 1964: he is invited to present speeches on Psychosynthesis at the International Congresses of Psychotherapy [6]

- 1965: he is one of the founders of the Italian Society of Psychosomatic Medicine

- 1967: he is invited to present a main lecture in the plenary session of the first International Psychosomatic Week in history

- he is part of the editorial board of the Journal of Humanistic Psychology and of the Journal of Transpersonal Psychology

This is also the time for publications. Three the most important ones that mark the symbolic fulfillment of the lines of research that he had cultivated since his youth:

- In 1965, he publishes his first book in English Psychosynthesis – A manual of principles and techniques, in which his studies on psychoanalysis and psychotherapy finds their systematic organization;

- The interest for American pragmatism and for the fundamental theme of will and for active techniques will give life to the Act of Will, published in 1973, and considered by many to be one of the very first coaching manuals;

- In the last days of his life, Assagioli was working on a book dedicated to psychology of the high and the Self. In this text, published with the title “Transpersonal development“, converge the reflections of an entire life on the different paths that human beings travel in search of their self-realization and self-transcendence.

Finally, this will also be the period in which Assagioli begin to train students from many parts of the world: those who will continue its work to the present day. Just one of them, tells in an interview an episode with which I like to close this short presentation of his figure.

This student says that Assagioli had a little boat on his desk and when the housekeeper woman dusted, it got turned around. He always put the boat back in the direction of the window, towards the open space, and once the student asked him why. He replied: “Because it represents adventure for me, I can start again at any time, change and call everything into question”. [7] Over the years, he repeated that he had not yet learned to live, that we never stop learning to live.

NOTE ___________________________

[1] P. Guggisberg Nocelli, Know, Love, Transform yourself, Psychosynthesis Books, Lugano, 2022

[2] G. Dattilo, P. Ferrucci, V. Reid Ferrucci, (edited by), Roberto Assagioli in his own words, Recorded by E. Smith, Ed. Istituto di Psicosintesi, Florence, 2019

[3] R. Assagioli, cit. in P. Giovetti, Roberto Assagioli, Ed. Mediterranee, Roma, 1995

[4] R. Assagioli, cit. in P. Giovetti, op. cit.

[5] R. Assagioli, Edited by C. A. Lombard, Freedom in Jail, Ed. Istituto di Psicosintesi, Florence, 2018

[6] R. Assagioli, Psychosynthesis and existential psychotherapy, Communication to the 5th International Congress of Psychotherapy, Vienna, 1961 and R. Assagioli, Synthesis in psychotherapy, Communication to the 6th International Congress of Psychotherapy, London 1964

[7] P. Giovetti, op. cit.